Big Tech Becomes the Gatekeeper as Programmers Grow Dependent on Platforms

July 25, 2025

Even though we’re now more than a decade into the media industry’s great disruption, the landscape remains in flux. Incumbent media businesses worth billions of dollars are still in the process of adapting to it, while new players seize the opportunity to get their own foothold.

The story told through the headlines of the press paint a picture of a long-running “Streaming Wars” focused primarily on content, as if a single SVOD service could somehow triumph over the others. While this has been a source of endless fascination for journalists, the most interesting and significant developments in the media industry over the past decade have been undertows, lurking beneath the surface until their ramifications burst forth in a way that’s suddenly no longer possible to ignore.

While industry observers were focused on the traditional TV networks taking the fight to Netflix with their own SVOD apps, much less attention was paid to the impact of so many new SVOD services launching at once. This ended up being the matter of real consequence, not whether consumers would abandon Netflix’s library for Disney’s in droves if given the opportunity to do so. A decade later, who won the Streaming Wars is still debated, but super-charged churn rates and sky-high customer acquisition costs have become facts of life.

This same dynamic is playing out again as focus shifts to the next hot topic in the industry: the “TV OS Wars.” Much like before it’s utterly impossible for one operating system to triumph over the others. But likewise, there is also a consequential story here, lurking below the surface but poised to make itself known.

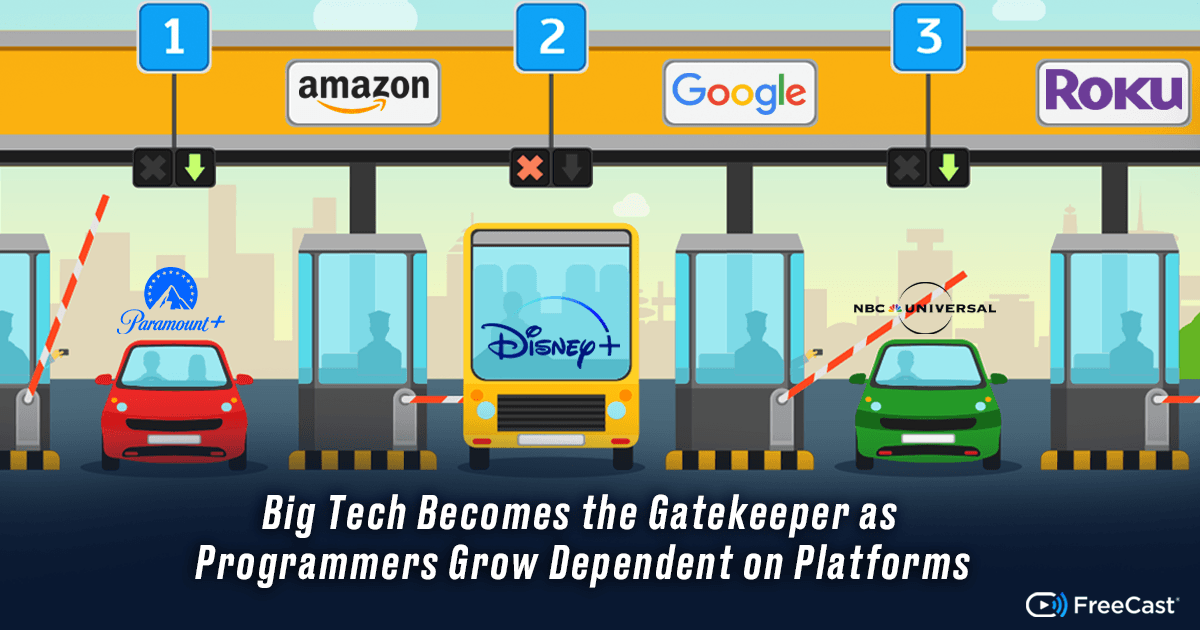

As linear TV reaches the tipping point and streaming takes over as the primary means through which consumers access video, those TV operating systems take on new significance. They are now central to the TV experience, not only for cord-cutters or alternative devices, but for nearly every media consumer and on nearly every new television sold in recent years. The neutrality of the cable cord has now been replaced by non-neutral platforms, each of which is pay-to-play, and each of which has its own commercial agenda.

Smart TVs, streaming sticks, set-top boxes, and more have long been little more than means for consumers to get to what they want to watch on whatever services they happen to use. But now programmers must pass through these platforms to reach their own audiences, and what seems like a subtle shift may prove to be one of the main stories of the coming years, particularly as traditional linear TV continues to recede.

The New Gatekeepers

It’s easy to get stuck in the early Netflix mindset; that a consumer who wants to watch a Disney movie will know to boot up Disney+ and find it. But so much media is consumed without a direct intention to view a specific title, and even when there is intention, there is now a new gauntlet of obstacles that can steer consumers elsewhere.

This is a huge change from the linear TV era. While there were certainly disputes over neighborhooding, and efforts to secure coveted low channel numbers on the cable dial, the old TV distributors did little to interfere with viewers as they flipped through the dial. Save for the occasional ad in the on-screen channel guide, viewers could browse or surf channels as they wished.

But a streaming-first television experience looks different from start to finish. When turning on a TV today, rather than being immediately greeted with a live linear channel, most viewers today find themselves on some sort of home screen. Some favored content of their own choosing may be there, but it’s also likely to be dominated by promoted content, pre-loaded and default streaming apps, and ads.

Research has shown, these aren’t like the ads and bloatware we’re used to, they often do steer consumer behavior. With so many FAST channel services out there, the one that comes pre-installed on a smart TV is the one most likely to be used. When a user wants to access a certain show or movie, the odds are much higher that something else could catch their eye and divert them when other video content is promoted before they can even in to an app.

Virtually all “TV” is now coming through smart devices, which means these ad-laden home screens are almost always consumers’ first stop now. To even have a chance at getting a viewer’s eyeballs, the big media companies are playing on big tech’s home turf. In fact, they very platforms are often owned by their competitors. Roku is almost synonymous with set-top boxes, Amazon manufactures Fire TV sets and streaming sticks, Google’s Android TV powers many third-party smart TV, and even Apple has a set-top device for those in its ecosystem.

Unlike the cable dial, which was more or less neutral territory, these platforms are not just controlled, but actively managed by these big tech firms with their own business interests. Worse yet, their portfolios increasingly include media assets of their own, which compete directly with legacy programmers. Their incentives are to steer consumers towards the options that make them the most money, meaning that the old school media companies themselves, when they attempt to compete for eyeballs, are not doing so on a level playing field.

The Peril for Programmers

As streaming takes over as the main means of media distribution, we’ve seen a “flattening” effect. Content used to be more stratified. There was free network TV, cable and satellite pay channels, premium movie channels like HBO… Netflix was more akin to the latter when it first began offering SVOD service, while user-generated content was the bottom of the barrel, an endless supply of cheaply-produced but generally low-quality junk content from YouTube, which was in a category of its own.

In a streaming-first world, these strata are all blurred together. Whether you want to watch re-runs of Seinfeld or the latest must-watch series from HBO, odds are you access them the same way: by paying for an SVOD service. AVOD and FAST services offer yet more content, with the only functional difference being the lack of a paywall.

YouTube is also a more formidable competitor in this environment. Smart TV platforms can put user-generated videos right alongside Hollywood’s latest and greatest. These days everyone has a smartphone capable of shooting decent quality video, affordable technology and tools allow amateurs to punch above their weight when it comes to production, and many content creators have built thriving businesses on free platforms like YouTube and Facebook.

In short, the move from cable and satellite TV to streaming has meant that when a kid wants something to watch, Mickey Mouse now has to compete with Mr. Beast.

That competition now includes a home field advantage; those that operate these streaming platforms are not neutral parties. So to compete with both first-party titles getting preferential treatment and viral content from celebrity creators, only marketing dollars can tip the scales back.

For programmers without Disney’s ad budget, the challenge is more difficult. Local broadcasters in particular are suffering, as new television sets steer consumers away from broadcast and towards FAST channels for free TV. The big media empires have plenty of resources, although they’re struggling to make their streaming offerings profitable as it is. But for small and medium-sized programmers, like broadcast stations, Diginets, independent cable channels, and others, this poses an existential threat.

The Need for Neutral Aggregation

Once again, the media industry has created its own monster. This time rather than an SVOD service cannibalizing its own revenues, they’ve created something akin to a bridge troll extracting a fee.

Consumers have long been clamoring for better search and navigation as the streaming ecosystem has fragmented. In light of the consumer struggle, an aggregation solution has arguably been just as much needed by programmers, who are wasting billions trying to re-invent the wheel, compete with one-another, and re-acquire the same customers over and over again.

Now, the need for a neutral, agnostic platform is becoming clear, and a critical priority for the media industry.

At FreeCast, we’ve long had a saying. “We’re Switzerland.” Always neutral. That’s been critical to our business and strategy. We want all programmers to be able to offer their content on our platform, and we want to be able to work with all the tech platforms too.

Our view has always been that the best way to solve the frustrations in the media industry is to keep things simple and easy for consumers, by eliminating the barriers and inconveniences that have emerged from fragmentation and competition among all the new streaming services.

Google, Amazon, Roku, Apple, and others can’t be Switzerland. They have dogs in the fight. They have their own business incentives. They have age-old battle lines just like the big media companies do.

The better approach is one of cooperation rather than competition, which has so far achieved little for any of the competitors involved, aside from driving up churn rates and customer acquisition costs.

That’s not to say that FreeCast isn’t a business with an aim of making money, but it has been thoughtfully designed to work specifically as that neutral party, recognizing the tremendous value having that neutral party represents to the wider industry.

By providing a valuable service to organizations that already have large user- or subscriber-bases, FreeCast is well positioned to be a low-cost vehicle for programmers to reach millions of consumers, and potentially even billions on a global scale. Working with telecoms and bandwidth providers in particular allows for a seamless integration of both communication and entertainment services, which makes the most conceptual and economic sense.